|

My debate with Aegis. (19 viewing) Cardoso, CyborgJesus, Drizel, fifi, gasto, Kartraith, Kristoff Greenwood, Kymatica, Labyrinth, madz3000, Maelkoth, Meshuggeth, neverquit, pureblueearth, Relic180, shot2pieces, straw prophet, VenusWorld, (1) Guest

| | |

|

TOPIC: My debate with Aegis.

|

|

Re:My debate with Aegis. 20 Hours, 45 Minutes ago

|

|

|

I am not sure I would

have started attacking aegis before they even began their debate.A link

to the Colbert forums would have sufficed and now, as I see it, the

debate is tainted. I would like to think this is an opportunity for the

movement to show it's intellect and ability to civilly disagree, and

allow any who would act in a manner not consistent with civility to

debase themselves. Remember we are promoting a change in consciousness,

We cannot exclude ourselves from this. I do not defend those who attack

us with malice, but I do point out the fact we need not attack back and

indeed by choosing not to we come out more credible.

my 2 cents:)

Be well!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Re:My debate with Aegis. 20 Hours, 25 Minutes ago

|

|

|

I just feel that it's

an inefficient use of our time, discussing ideas with someone who has

such an ignorant opinion on his relationship to the environment and the

planet.

I am probably wrong. Please (if you're able to) delete my posts if you think they distract from intention of the thread.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Re:My debate with Aegis. 19 Hours, 41 Minutes ago

|

|

|

I don't understand why

this thread is on page two before the debate has even begun. Perhaps a

mod should split out these posts, since they don't really pertain to the

debate we are supposed to be having.

|

|

aegis

Level 1 Poster

Posts: 33

|

|

|

|

|

Re:My debate with Aegis. 19 Hours, 33 Minutes ago

|

|

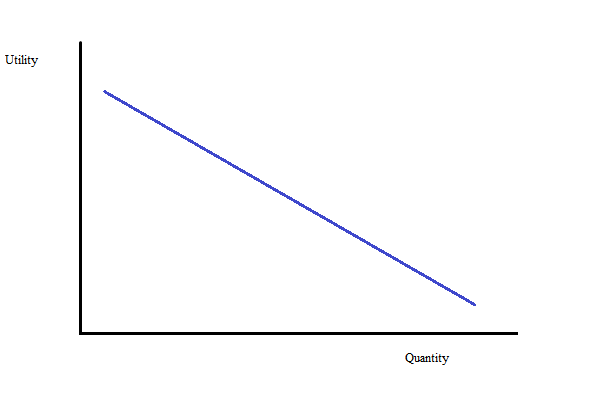

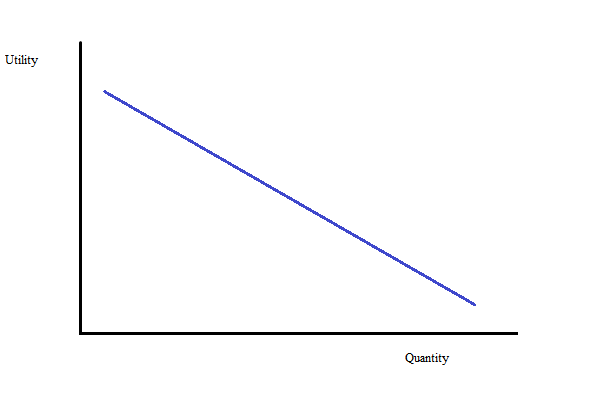

Before getting into all

of the specifics of money, price, and equilibrium, first I would like

to talk about utility. Utility is the benefit that a person gets from

having/using an item. It is not happiness, but ‘usefulness’. This is the

root of economics; not the study of money, but the study of choice

between two or more options. We base all of these choices off of

utility.

Now, think about your utility of any item. For the first bit of it, you

get a lot of use. As you get more of it, your usefulness of each one

goes down. In terms of food, think about an apple; for your first apple

you love it. Your second apple is good too, but not as good as the

first.

By the time I am giving you 10 or 12 apples, you really would rather

trade some of these apples for something else, since that new item would

be at the top of the utility; you would be getting more use out of one

of that other item than you might be getting out of 2 apples. This is

true even if your 1st apple gives you more utility than your 1st banana

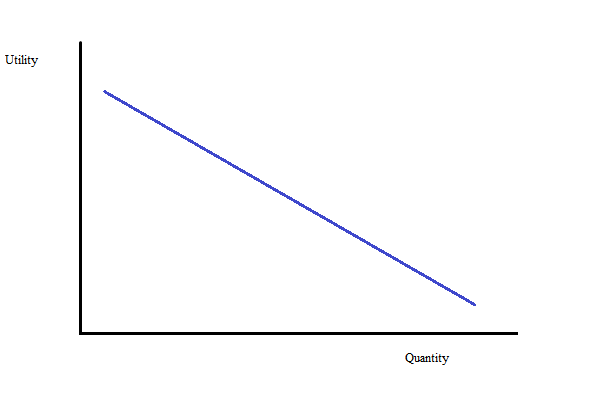

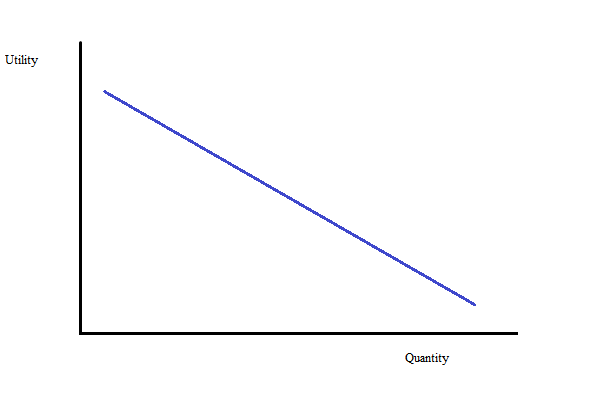

(as the other item). So accepting this, your basic utility curve is

downward sloping.

By the time you get to very high quantity, your benefit of having each additional item is basically nil.

Now, let’s think about present and future value of an item. After all,

you could choose to get an apple now, or get it later. But it is better

to think about this in terms of durable goods; you could get a car now

or later. But what happens to the utility of the car over time? How does

the utility of having a car today compare to the utility of having a

car, say, a year from now?

Well, the present value of that car is higher than the future utility.

Why? Because you would be getting usefulness of that car between today

and a year from now. All of that utility adds together, and so the total

benefit of having the car is higher now than if you were to wait.

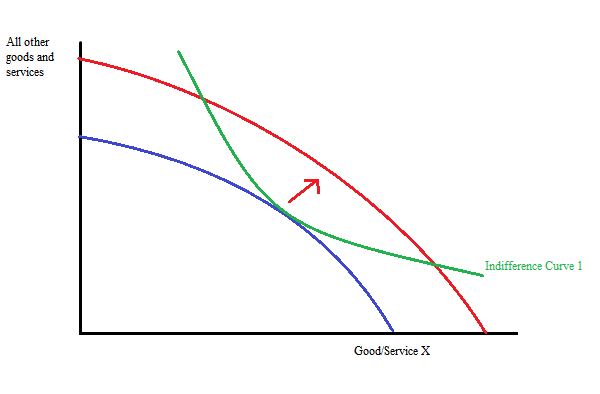

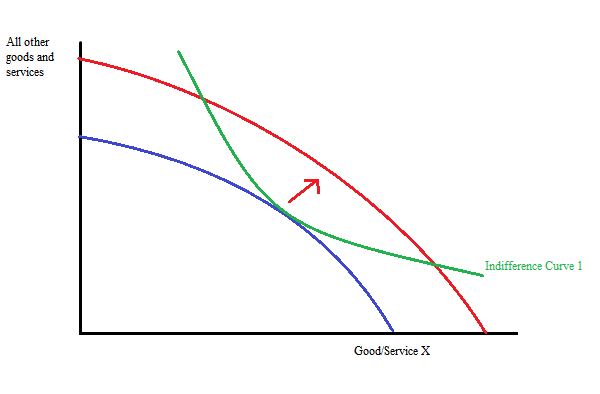

If you look at your utility for an item, you know that its value still

does go up as you keep adding to it, even if that value keeps

diminishing. This is true for all goods and services. So if you want to

know at what points you will have the exact same amount of utility when

comparing two items, or one item against the combined weight of all

items, you get an indifference curve.

As you keep exchanging everything else for good X, it takes more and

more of good X to give you the same benefit. At all points on this

curve, the person is equally as happy.

The next concept is opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of doing

something or producing something is all other things that you could have

instead done with those resources. For example, if I have a lump of

gold, the opportunity cost of me turning that gold into jewelry would be

that I can no longer turn that same lump of gold into plating for

electrical components. If at a later date I decide that I would rather

have the plated electrical components, the opportunity cost of me

melting down the earrings I made earlier is that I no longer have the

earrings. The best way to compare opportunity cost is in units of

utility; I can decide whether I am going to make the earrings or the

electrical plating (or any other use for gold you can think of) based on

which option is going to give me the highest utility.

Keeping that in mind, using resources, or all resources for that matter,

for the production of another results in the opportunity cost of not

being able to use those resources for all other things. But then we get

into how efficiency of the production process can help retain utility as

much as possible.

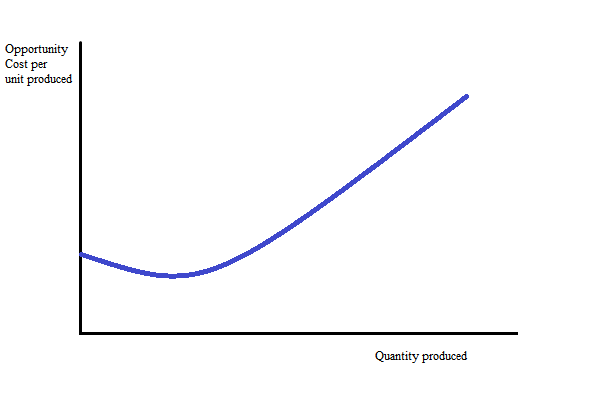

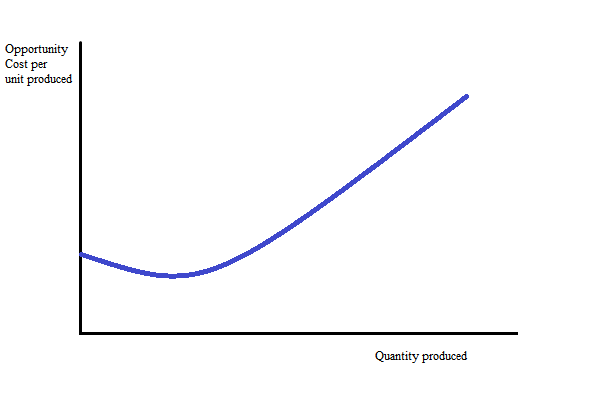

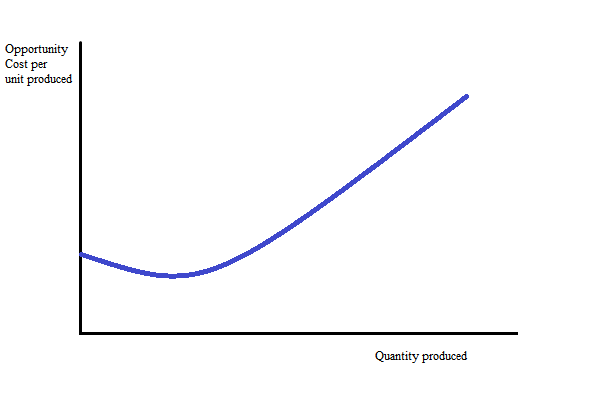

For the first unit of production, it is going to cost everything else

the most. After all, you have to build the factory, get all the

machines, and all the raw materials together to churn out your first

item. However, the second item no longer has this requirement of

building all of that stuff, its only real cost is the additional raw

materials. Each additional unit of production is similarly cheap, up

until a point.

At a certain level of production, you will be using all of the machines

and factory floor space you can possibly use. In order to increase

production by one more unit, you are going to have to add another

machine, increase factory floor space, ect. This means that you are

going to have to divert more resources away from making other things;

the opportunity cost of creating each additional unit is going to go up.

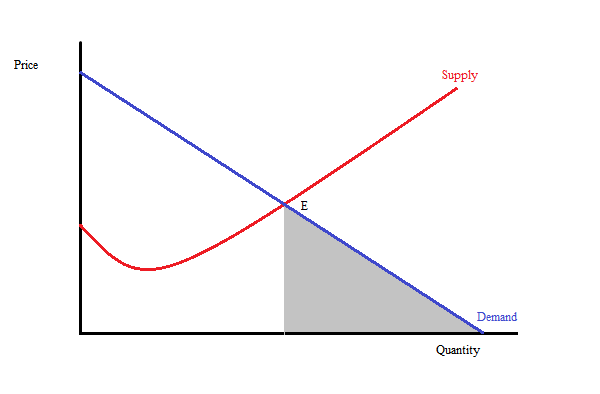

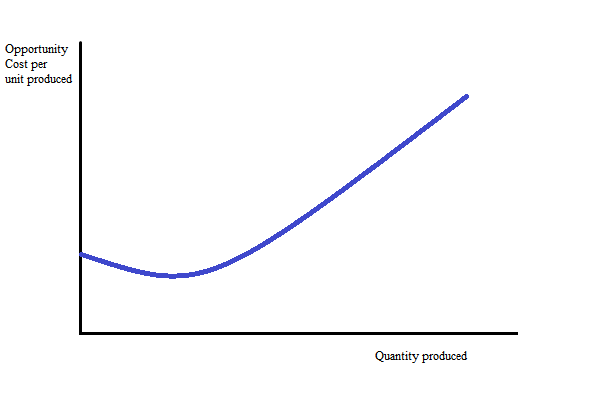

This can be expressed as a function of cost and production, and when

you make a graph out of it, it looks like this:

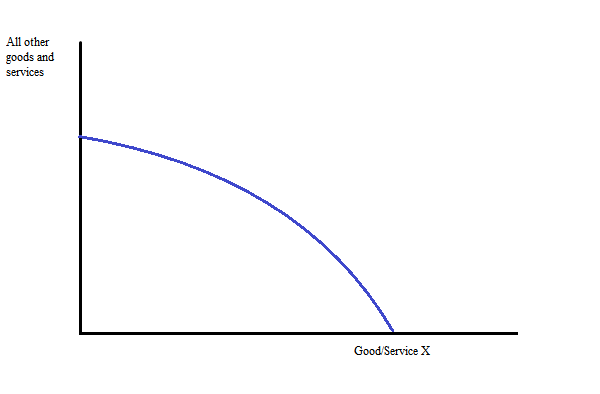

Now, at a certain point, the opportunity cost of making another one of

these things is going to be less than the utility that you get from

having it. After all, you could be using those resources to make all

those other things, which will give you more utility per unit. So when

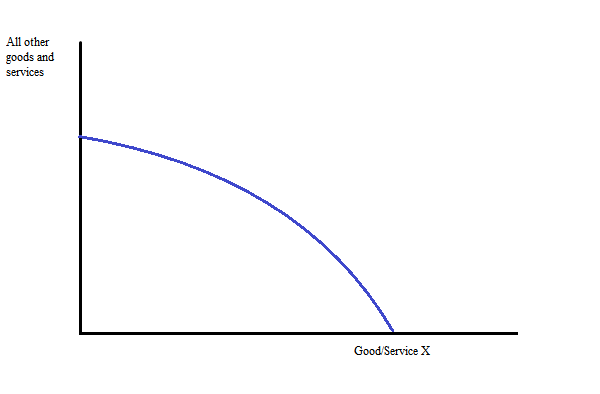

you look at everything you could be doing with all of your resources,

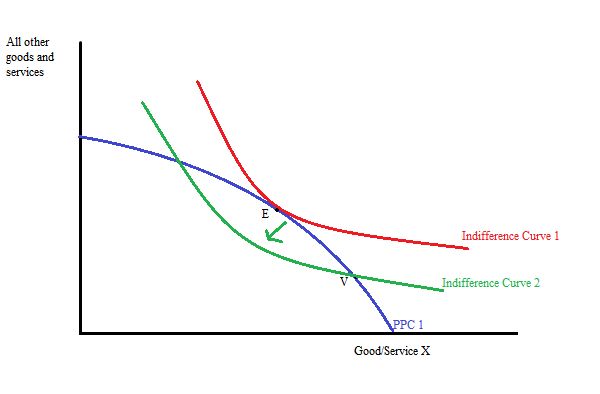

you get a Production Possibilities Curve, which looks like this:

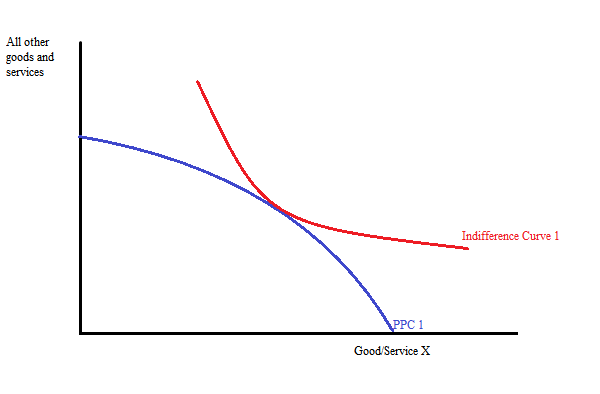

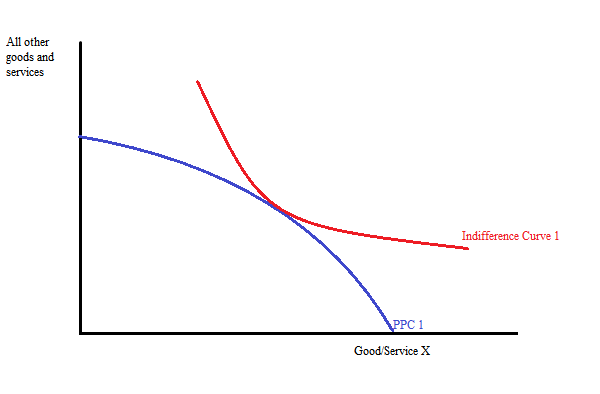

Now, if you want to find where on this curve you should be producing

good X and all other goods/services to maximize your utility, you put

your indifference curve on the highest point out that you can apply your

indifference curve.

Well, that didn’t help much. There are two points where the indifference

curve and the Production Possibilities Curve intersect. So how do we

choose the best point?

Well, our goal is to maximize utility. Every time we move our utility curve out, it means that we have more total utility. So…

The red curve is preferred to the blue curve, the outward shift is an

increase in total utility. And so to find our optimal point on the

production possibilities curve, we just have to shift our indifference

curve outward until it only touches at one point.

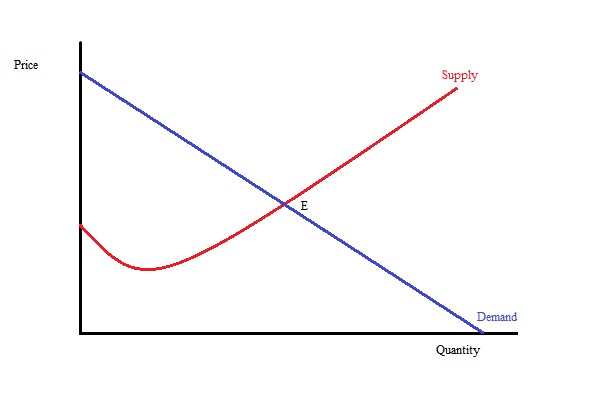

Great, we just found the optimal point to balance our resources. So where would this point be on our marginal cost graph?

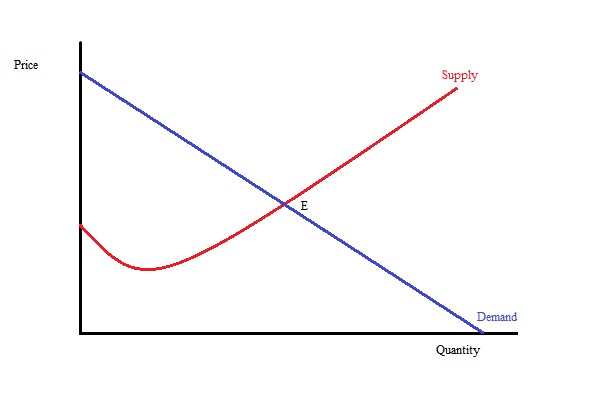

Well, the easiest way to do that would be to put our utility curve:

Onto our marginal cost curve:

And where they intercect would show us the usage of resources for the

production of our one good against the production of all other goods.

You will note that the labeling has changed. The price of the good is

the reflection of the opportunity cost of producing that good or service

against the opportunity cost/utility of producing all other goods with

those resources. Demand is nothing but an expression of utility of the

economy as a whole.

In order to express the opportunity cost or utility of an item, you need

a unit which is convertible across ALL goods and services AND across

both cost and benefit (utility). The unit that you need to use is money.

Money is nothing but a medium of exchange, a standard unit by which you

can measure other things.

So how does our money work? More importantly, why does our money work?

Well, for a long time each dollar was backed by gold or silver, because

it was believed that gold and silver have intrinsic value that can be

exchanged for other things. If you brought a dollar to a bank, they were

legally required to be able to give you its value in gold (it was

called “specie”). Over time, we began to realize that gold and silver

had other value, and that there was a market for them as well.

Since the utility of one dollar’s worth of gold exchanged for any item

might be worth less than that same unit of gold plated onto electronics

devices and put to use, eventually things got out of whack. Gold could

not be found to use as backing for money because the utility of using it

for other things was higher than using it for specie. Silver eventually

had similar problems. So at a certain point, it was decided to abandon

that system entirely.

Instead, we developed a system of “debt based money”. The Federal

Reserve loans money to banks, who in turn lend it out to citizens and

businesses. These citizens and businesses are required to provide

collateral for these loans; the collateral can be pretty much anything

of value. The person/business borrows against the value of that item,

and in turn is given money. So in reality, the money that they receive

is backed by the item they borrowed against, rather than simply gold or

silver.

All of that value is kept in the balance sheets, and it is freely

exchanged for different items of value. This is why money as debt works;

since each dollar is backed by a dollar of “stuff” at some point along

the chain, by holding that dollar society as a whole owes that person

holding the dollar exactly one dollar worth of “stuff”.

This is extremely convenient, because it allows us to manage the utility

and opportunity cost of all items in a single medium. Because all

goods, services, materials, capital, and everything else is expressed in

the same Supply/Demand function working for each item, all goods and

services can be applied to the same production possibilities curve, and

we can optimize the total utility for all items by constantly adjusting

the equilibrium of the supply/demand curves to reflect the opportunity

costs changing of all other items in real time, which we do.

How? Simply put, through the concept of “profit”. Keep in mind that the

marginal cost curve that we already went over is based on what could be

done with those resources elsewhere; it is the opportunity cost of

producing that item. The demand curve expresses the utility added to the

combined utility of everyone; each additional unit that the economy as a

whole receives is lower than the previous. Each time that you increase

production, the marginal cost (utility you are losing by producing this

item instead of all others, the opportunity cost) goes up (after the

minimum point, which we already discussed).

Profit is maximized when marginal cost equals demand. One unit less, you

could be producing an item with a marginal cost below the aggregate

utility of the economy as a whole. One unit more, you are applying

resources that could be used to make something that the aggregate

economy would receive a higher utility from.

Now, this means that profit has been maximized, and (hopefully) revenue

of the producer is higher than the cost of producing the items it just

did. What happens to this profit? By and large, it is re-invested into

the production, to increase efficiency, reduce the opportunity cost, and

increase the profit at the next cycle. But keep in mind that this

profit is money; it is a debt that society as a whole owes to the person

who holds it. It is resources. The firm could either use these

resources to improve itself; increase efficiency, increase its

technology, ect, or it could invest it in another venture.

If it invests these resources in another venture, it does so because the

utility gained from whatever this other venture produces is higher per

unit of resource added than the firm which is giving it these resources;

the firm which produced the profit is looking for the highest return on

its investment.

Seeking out the highest return on investment is both an activity of

firms and individuals; the return on investment is resources in itself,

which can be exchanged for whatever provides the highest utility, which

in turn provides the highest benefit. Every time the decision is made

that the most utility can be added by expanding productive capacity, the

production possibilities curve expands outward:

Since the curve has expanded outward, you can shift your indifference

curve outward to where it is efficient again, and the total utility of

everyone in the economy is expanded. This is economic growth.

Growth is limited, however, by the future value of utility. People and

firms are given a choice between using its resources to increase its

utility in the future, or get more utility now. Investment in the future

means that the expected return on the investment will not only be

higher than the current utility, but also higher than the future value,

minus the utility that could have been had by getting a utility-yielding

good or service today. This is a balancing act in and of itself;

balancing growth.

I am sure I am forgetting something in this, but I will be reminded of

it later and include it in this post (with an update tag). |

|

aegis

Level 1 Poster

Posts: 33

|

|

|

|

|

Re:My debate with Aegis. 19 Hours, 28 Minutes ago

|

|

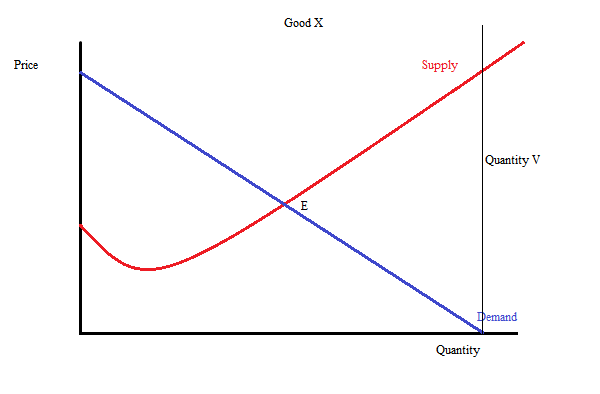

Now, let’s look at the

proposals of the Venus Project. Its first claim is that the current

supply and demand balance results in a lot of demand being unsatisfied.

The grey shaded box represents all of the utility lost by producing at

the equilibrium point, E. Just because we found E to be the most

efficient production point does not mean that this other demand just

goes away; it represents utility that will not be realized.

According to the Venus Project, we should instead produce this item at the point where demand is fully satisfied.

This way, everybody gets the amount of Good X that they want. But let’s

look at what this does to the Production Possibilities Curve:

Quantity V (the quantity of production that has all demand satisfied) is

farther along the PPC than Quantity E. Resources need to be diverted

away from making other things to create these additional units of Good

X. So when we look at the indifference curve of the economy that results

in the utility had by completely satisfying the demand for X, we get

this:

The curve as a whole shifted inwards. Since we already established that

you want to be on the farthest out curve that you possibly can, we know

that the combined utility for all goods and services is now lower than

it was before. Why is this worse off? Well, let’s look at Good Y, which

uses some of the same resources as Good X

Since we just diverted resources away from Y to produce more of X, the

quantity produced of Y is now lower than E. On the production

possibilities curve, it is here:

Just like X, the total utility is lower, but it is now caused by a

decrease in the production of the item rather than an increase. This is

repeated thousands of times across all goods and services that use the

same resources as X.

But what if we were able to create a technological breakthrough that

allowed X to be produced with fewer resources? That would cause the

production possibilities curve to shift outward, and help correct the

problem:

When we apply Quantity V to this graph for the production of Good X (so demand for X is fully satisfied), we get this:

The utility curve still isn’t quite optimal (it still touches the

production possibilities curve in two places), but at least total

utility is higher. Let’s look at the effect on Good Y

There was no shift in this production possibilities curve, because the

technological advance that we had didn’t increase our ability to produce

good Y if we diverted all of our resources to it. However, it means

that we get more resources free to produce good Y that now don’t need to

be used to produce good X, so Indifference Curve V is allowed to shift

outward to Indifference Curve V 2. While this is an improvement over

Indifference Curve V, you can still see that utility as a whole is still

significantly lower than it had been when resources were optimally

distributed to begin with (the difference between optimality and reality

from Good X’s new graph is magnified here).

Total utility will remain lower than optimal until you have enough

technological improvements in the production of good X that all demand

is satisfied using no more resources than were used at the optimal level

to begin with. As we all know, technological advancement, while rapid,

still takes time. More importantly, it takes resources.

Resources you use to advance one technology cannot be used to advance a

different one. By putting all of our resources into technological

advancements into Good X to increase its efficiency to the point where

we can finally see a total increase of utility, we are taking away from

the development of all other technologies. If you allow all things to be

produced at equilibrium, technologies advance at the optimal level;

resources are applied to advancing the technologies that will give the

greatest boosts to total utility.

Now we are getting into the problem of present and future value again.

By meeting the demand for X at the cost of utility from Y, total utility

is reduced. So resources are diverted from the developing of all other

technologies into developing capacity for X in order to get our utility

back to our original equilibrium. Eventually, perhaps it is possible to

get the production opportunity cost of X back down to the equilibrium

point and produce enough to both satisfy total demand and not cost more

than its marginal value to other goods (namely in our example, good Y).

But all of that takes time, it could take 50 years just to elevate the

production of one good up to the point where our total utility is up to

our original equilibrium. But even then, we are worse off. We had to

wait 50 years to have utility that we rightfully should have had access

to from the get-go. We have 50 years of utility wasted, and that is

before you consider the extra loss you got from not expanding the

productive capacity of everything else, just so you could fully satisfy

the demand of one good (Good X).

No matter how you cut it, no matter what angle you analyze it from, you are worse off in this second arrangement, hands down.

Some other problems arise from the Venus Project: (this is going to be more of a list than full explanations)

There is no reason to conserve anything. I have been told by supporters

that goods produced under this arrangement would be both much more

durable than what we have under a market system (for example, a car

would not break after 100k miles), and that technological advancements

would be implemented into production and available to all immediately.

These are counter goals; if I have a car built that can last for 50

years, it is going to need more resources to build than a car that will

last 10 years. So each car produced is going to be more

resource-intensive than it otherwise would need to be. At the same time,

technological advances take place all the time. Every year, a new car

could be built that is better than the car produced a year before. So

now you have all these cars that are supposed to last 50 years that

everybody is trading in for these new cars after 1 year. All of those

resources that were used to make it last a long time were completely

wasted, and it means that all cars on the road should be replaced

literally every year. This is the same for pretty much every durable

product, you are saying that the resources should be invested that would

extend the lives, while at the same time saying that their lives should

be constantly cut short to advance the stock held by the People at any

given time.

So instead of using the current resources, which involves replacing

roughly 7% of all cars on the road every year (plus extra to allow for

growth), 100% of all cars would need to be replaced every year. Assuming

that you recycle literally every component out of every single car, you

still would be required to have 93% more cars built every year than you

would under a market system. This is because you cannot recycle a car

at the same time you are building it, you have to build the car, give it

to the person, who in turn gives you their “old” car, which you can

then recycle. Since 97% more cars are built every year instead of 7%,

you have to use more than 13 times as many resources JUST for production

of cars, and all of those resources are going to come from every other

thing that could be produced. This applies to all goods and services;

you are wasting many, many times more resources than you otherwise would

have to on turnover alone. |

|

aegis

Level 1 Poster

Posts: 33

|

|

|

|

|

Re:My debate with Aegis. 19 Hours, 25 Minutes ago

|

|

|

Now, before I am called

out for ignoring reality, let’s look at reality. It is clear that the

system does not work at perfect equilibrium; there is waste in the

system that is lower than the cost of recovery. There are a million

cases where the price and opportunity cost that is found by the market

is different than the actual cost or benefit to society. The main case

where the actual cost is higher is pollution; the true cost to all

things is not expressed in the market price for things that pollute. The

main case when the actual cost is much lower is education; the cost on

society of education is MUCH lower than what people have to actually pay

in order to get it.

I already showed that getting rid of money altogether does not solve

this problem. So what does? At the risk of sounding cheesy, democracy

does. We are able to tax and spend money, meaning convertible resources.

So if it is determined that the manufacture of a car produces the

equivalent of $100 in damage to the environment than is accounted for in

the price, we are able to tax that car for $100, and use the proceeds

to help reverse the damage. On the other side, if we determine that the

real “cost” of education is $500 less than it is under the market, we

can subsidize the cost of education by $500 out of public funds, which

lowers the cost to all, and results in more people getting an education.

The real work that needs to be done is not destroying the system we

have, but working to make sure it runs as well as it possibly can.

People who have a passion need to follow that passion; if you love

building cars, train to be an automotive engineer to help find a more

efficient way to build cars to increase their utility while decreasing

the resource-intensiveness. I personally have a passion for politics and

economics, and so I divert my energies into trying to get the

bureaucratic system as a whole to run more efficiently and better

allocate those public resources to the most efficient allocation to

reflect total cost and benefits.

|

|

aegis

Level 1 Poster

Posts: 33

|

|

|

|

|

Re:My debate with Aegis. 18 Hours, 42 Minutes ago

|

|

|

Economics is based off

of scarcity (supply and demand) and the monetary system. We have the

technology to remove scarcity (of the necessities of life) for everyone. The monetary system is an out-dated social construct that was only useful in allowing humanity to progress this far. Both Scarcity and The Monetary System are now irrelevant. Therefore --> Economics is now irrelevant.

You inevitably will defend economics since you have likely invested much

time and effort into learning. I challenge you to be objective in your

assessment of this topic instead of fervently defending your area of

so-called "expertise". Try to re-read this post without any personal

bias. If you have questions about any of the specifics of this post, I

(we) would be more than willing to explain to you why they are accurate.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Re:My debate with Aegis. 18 Hours, 38 Minutes ago

|

|

|

shawn111 wrote:

Economics is based off of scarcity (supply and

demand) and the monetary system. We have the technology to remove

scarcity (of the necessities of life) for everyone. The monetary system is an out-dated social construct that was only useful in allowing humanity to progress this far. Both Scarcity and The Monetary System are now irrelevant. Therefore --> Economics is now irrelevant.

You inevitably will defend economics since you have likely invested much

time and effort into learning. I challenge you to be objective in your

assessment of this topic instead of fervently defending your area of

so-called "expertise". Try to re-read this post without any personal

bias. If you have questions about any of the specifics of this post, I

(we) would be more than willing to explain to you why they are accurate.

You did not read any of the three posts that I spent a lot of time

preparing. Please only respond to this topic with constructive posts.

This thread is going to require extremely heavy moderation to avoid these problems.

|

|

aegis

Level 1 Poster

Posts: 33

|

|

|

|

|

Re:My debate with Aegis. 18 Hours, 31 Minutes ago

|

|

aegis wrote:

Before getting into all of the specifics of

money, price, and equilibrium, first I would like to talk about utility.

Utility is the benefit that a person gets from having/using an item.

It is not happiness, but ‘usefulness’. This is the root of economics;

not the study of money, but the study of choice between two or more

options. We base all of these choices off of utility.

Now, think about your utility of any item. For the first bit of it, you

get a lot of use. As you get more of it, your usefulness of each one

goes down. In terms of food, think about an apple; for your first apple

you love it. Your second apple is good too, but not as good as the

first.

By the time I am giving you 10 or 12 apples, you really would rather

trade some of these apples for something else, since that new item would

be at the top of the utility; you would be getting more use out of one

of that other item than you might be getting out of 2 apples. This is

true even if your 1st apple gives you more utility than your 1st banana

(as the other item). So accepting this, your basic utility curve is

downward sloping.

By the time you get to very high quantity, your benefit of having each additional item is basically nil.

Now, let’s think about present and future value of an item. After all,

you could choose to get an apple now, or get it later. But it is better

to think about this in terms of durable goods; you could get a car now

or later. But what happens to the utility of the car over time? How does

the utility of having a car today compare to the utility of having a

car, say, a year from now?

Well, the present value of that car is higher than the future utility.

Why? Because you would be getting usefulness of that car between today

and a year from now. All of that utility adds together, and so the total

benefit of having the car is higher now than if you were to wait.

If you look at your utility for an item, you know that its value still

does go up as you keep adding to it, even if that value keeps

diminishing. This is true for all goods and services. So if you want to

know at what points you will have the exact same amount of utility when

comparing two items, or one item against the combined weight of all

items, you get an indifference curve.

As you keep exchanging everything else for good X, it takes more and

more of good X to give you the same benefit. At all points on this

curve, the person is equally as happy.

The next concept is opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of doing

something or producing something is all other things that you could have

instead done with those resources. For example, if I have a lump of

gold, the opportunity cost of me turning that gold into jewelry would be

that I can no longer turn that same lump of gold into plating for

electrical components. If at a later date I decide that I would rather

have the plated electrical components, the opportunity cost of me

melting down the earrings I made earlier is that I no longer have the

earrings. The best way to compare opportunity cost is in units of

utility; I can decide whether I am going to make the earrings or the

electrical plating (or any other use for gold you can think of) based on

which option is going to give me the highest utility.

Keeping that in mind, using resources, or all resources for that matter,

for the production of another results in the opportunity cost of not

being able to use those resources for all other things. But then we get

into how efficiency of the production process can help retain utility as

much as possible.

For the first unit of production, it is going to cost everything else

the most. After all, you have to build the factory, get all the

machines, and all the raw materials together to churn out your first

item. However, the second item no longer has this requirement of

building all of that stuff, its only real cost is the additional raw

materials. Each additional unit of production is similarly cheap, up

until a point.

At a certain level of production, you will be using all of the machines

and factory floor space you can possibly use. In order to increase

production by one more unit, you are going to have to add another

machine, increase factory floor space, ect. This means that you are

going to have to divert more resources away from making other things;

the opportunity cost of creating each additional unit is going to go up.

This can be expressed as a function of cost and production, and when

you make a graph out of it, it looks like this:

Now, at a certain point, the opportunity cost of making another one of

these things is going to be less than the utility that you get from

having it. After all, you could be using those resources to make all

those other things, which will give you more utility per unit. So when

you look at everything you could be doing with all of your resources,

you get a Production Possibilities Curve, which looks like this:

Now, if you want to find where on this curve you should be producing

good X and all other goods/services to maximize your utility, you put

your indifference curve on the highest point out that you can apply your

indifference curve.

Well, that didn’t help much. There are two points where the indifference

curve and the Production Possibilities Curve intersect. So how do we

choose the best point?

Well, our goal is to maximize utility. Every time we move our utility curve out, it means that we have more total utility. So…

The red curve is preferred to the blue curve, the outward shift is an

increase in total utility. And so to find our optimal point on the

production possibilities curve, we just have to shift our indifference

curve outward until it only touches at one point.

Great, we just found the optimal point to balance our resources. So where would this point be on our marginal cost graph?

Well, the easiest way to do that would be to put our utility curve:

Onto our marginal cost curve:

And where they intercect would show us the usage of resources for the

production of our one good against the production of all other goods.

You will note that the labeling has changed. The price of the good is

the reflection of the opportunity cost of producing that good or service

against the opportunity cost/utility of producing all other goods with

those resources. Demand is nothing but an expression of utility of the

economy as a whole.

In order to express the opportunity cost or utility of an item, you need

a unit which is convertible across ALL goods and services AND across

both cost and benefit (utility). The unit that you need to use is money.

Money is nothing but a medium of exchange, a standard unit by which you

can measure other things.

You could of saved yourself a lot of trouble with the college lecture.

Most of this stuff we already know, but I do not agree with your

conclusion at all. Money is more then just a medium of exchange. It is a

means that resources can be squandered, overused, hoarded. Etc. I see

you talk about profit down here a bit so I will save my comments for

that.

So how does our money work? More importantly, why

does our money work? Well, for a long time each dollar was backed by

gold or silver, because it was believed that gold and silver have

intrinsic value that can be exchanged for other things. If you brought a

dollar to a bank, they were legally required to be able to give you its

value in gold (it was called “specie”). Over time, we began to realize

that gold and silver had other value, and that there was a market for

them as well.

Since the utility of one dollar’s worth of gold exchanged for any item

might be worth less than that same unit of gold plated onto electronics

devices and put to use, eventually things got out of whack. Gold could

not be found to use as backing for money because the utility of using it

for other things was higher than using it for specie. Silver eventually

had similar problems. So at a certain point, it was decided to abandon

that system entirely.

Instead, we developed a system of “debt based money”. The Federal

Reserve loans money to banks, who in turn lend it out to citizens and

businesses. These citizens and businesses are required to provide

collateral for these loans; the collateral can be pretty much anything

of value. The person/business borrows against the value of that item,

and in turn is given money. So in reality, the money that they receive

is backed by the item they borrowed against, rather than simply gold or

silver.

All of that value is kept in the balance sheets, and it is freely

exchanged for different items of value. This is why money as debt works;

since each dollar is backed by a dollar of “stuff” at some point along

the chain, by holding that dollar society as a whole owes that person

holding the dollar exactly one dollar worth of “stuff”.

Yes, and oddly enough in all of these "systems" that are supposed to be

"the most fair way" there are always small groups of people who own 90%

of the wealth and large groups that have to somehow split the 10%. I do

not call that a functioning system. I am sure the wealthy think it's

working just fine.

This is extremely convenient, because it allows

us to manage the utility and opportunity cost of all items in a single

medium. Because all goods, services, materials, capital, and everything

else is expressed in the same Supply/Demand function working for each

item, all goods and services can be applied to the same production

possibilities curve, and we can optimize the total utility for all items

by constantly adjusting the equilibrium of the supply/demand curves to

reflect the opportunity costs changing of all other items in real time,

which we do.

Ok... yeah it's extremely convenient, for the banks. Nevermind the fact

that the money to pay back debts that are issued with interest does not

exist in the system in the first place...

How? Simply put, through the concept of “profit”.

Keep in mind that the marginal cost curve that we already went over is

based on what could be done with those resources elsewhere; it is the

opportunity cost of producing that item. The demand curve expresses the

utility added to the combined utility of everyone; each additional unit

that the economy as a whole receives is lower than the previous. Each

time that you increase production, the marginal cost (utility you are

losing by producing this item instead of all others, the opportunity

cost) goes up (after the minimum point, which we already discussed).

Profit is the root reason for all money systems being corrupted. Again.

And again. And again. And again. And again. It is also what creates the

disequilibrium because as soon as people are handing over more units

(money) then something is actually worth in resources the imbalances

start. But anyone in a Capitalist system has to find ways to get more

then they give because of the way the system is set up. As time

progresses the system gets more and more corrupt. Profit as a motive has

no concern for anything else. Including pollution, inhumane working

conditions, it influences politics and leads to wars. Virtually all of

mankind's problems can be directly linked to profit and the pursuit of

it.

Profit is maximized when marginal cost equals

demand. One unit less, you could be producing an item with a marginal

cost below the aggregate utility of the economy as a whole. One unit

more, you are applying resources that could be used to make something

that the aggregate economy would receive a higher utility from.

You make it all sound so simple. But in practice "demand" can be

artificially created. And is. Advertising industries engage in what

amounts to brainwashing to convince you to buy products you don't need

that in many cases are actually harmful to you. (Like having Edward

Bernays figure out how to get women to smoke.) As long as you have a

profit motive, advertising, scams and theft will be present.

Now, this means that profit has been maximized,

and (hopefully) revenue of the producer is higher than the cost of

producing the items it just did. What happens to this profit? By and

large, it is re-invested into the production, to increase efficiency,

reduce the opportunity cost, and increase the profit at the next cycle.

But keep in mind that this profit is money; it is a debt that society as

a whole owes to the person who holds it. It is resources. The firm

could either use these resources to improve itself; increase efficiency,

increase its technology, ect, or it could invest it in another venture.

Lets not forget all the money invested in pursuit of control over the

government through political campaigns and lobbying to ensure maximized

profit regardless of the consequences to other human beings.

If it invests these resources in another venture,

it does so because the utility gained from whatever this other venture

produces is higher per unit of resource added than the firm which is

giving it these resources; the firm which produced the profit is looking

for the highest return on its investment.

Seeking out the highest return on investment is both an activity of

firms and individuals; the return on investment is resources in itself,

which can be exchanged for whatever provides the highest utility, which

in turn provides the highest benefit. Every time the decision is made

that the most utility can be added by expanding productive capacity, the

production possibilities curve expands outward:

Since the curve has expanded outward, you can shift your indifference

curve outward to where it is efficient again, and the total utility of

everyone in the economy is expanded. This is economic growth.

Growth is limited, however, by the future value of utility. People and

firms are given a choice between using its resources to increase its

utility in the future, or get more utility now. Investment in the future

means that the expected return on the investment will not only be

higher than the current utility, but also higher than the future value,

minus the utility that could have been had by getting a utility-yielding

good or service today. This is a balancing act in and of itself;

balancing growth.

I am sure I am forgetting something in this, but I will be reminded of

it later and include it in this post (with an update tag).

So far I am seeing a lot of flowery technical language that is largely

missing the point. It seems you are trying to establish some things as

reality with a few nice looking graphs that are not based on any actual

data. You are creating data for later use in a debate that you have

convieniently designed to make your points with but there are far too

many variables that you are glossing over.

|

|

|

|

Neil Kiernan-

Official spokesman for the Venus Project.

v-radio.org/ |

|

|

Re:My debate with Aegis. 18 Hours, 13 Minutes ago

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The YOU is virtual, there is no such

thing as true intelligence since technically yours is artificial

as-well. Consciousness is not physical, it is generated constantly by

you're brain based on you're conectome virtually in a constant feedback

loop. And as such it is emulatable and even portable. |

|

|

| | |

Moderators: Folklorist, , moderator, DarkDancer, , apollo, Mihaela, moderator3, moderator4, moderator11, moderator12, moderator13, moderator15, moderator19, moderator21, moderator23, moderator27, moderator29, moderator30, moderator32, moderator34, moderator35, moderator36, moderator37, moderator38, moderator55, moderator40, moderator43, moderator58 |

|

|